Take a single strand of human hair. Now, imagine slicing that hair lengthwise into 50 equal pieces. One of those tiny slivers represents roughly one micron. In the realm of high-end industrial production, a variation of even a few microns can mean the difference between a jet engine that runs for decades and one that fails catastrophically.

The Evolution of Measurement

To build accurately, you must first measure accurately. The history of manufacturing is effectively a history of metrology—the science of measurement. In the early days of the Industrial Revolution, calipers and micrometers allowed machinists to work within thousandths of an inch. While impressive for the 19th century, this relied heavily on the skill and tactile “feel” of the operator.

The introduction of Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) in the mid-20th century marked a pivotal shift. These machines used physical probes to touch points on an object, creating a digital map of its geometry. This removed much of the human error associated with hand tools.

However, physical probes have limitations. They are slow and can distort soft materials. Today, the evolution continues with non-contact metrology. Optical scanners and laser trackers capture millions of data points in seconds, creating 3D point clouds that compare the manufactured part against the original CAD (Computer-Aided Design) model in real-time. This shift from manual verification to digital validation is the foundation upon which micron-level accuracy is built.

Technologies Driving Precision

The machinery used to cut, shape, and finish materials has advanced alongside measurement tools. Several key technologies are responsible for the incredible tolerances seen in factories today.

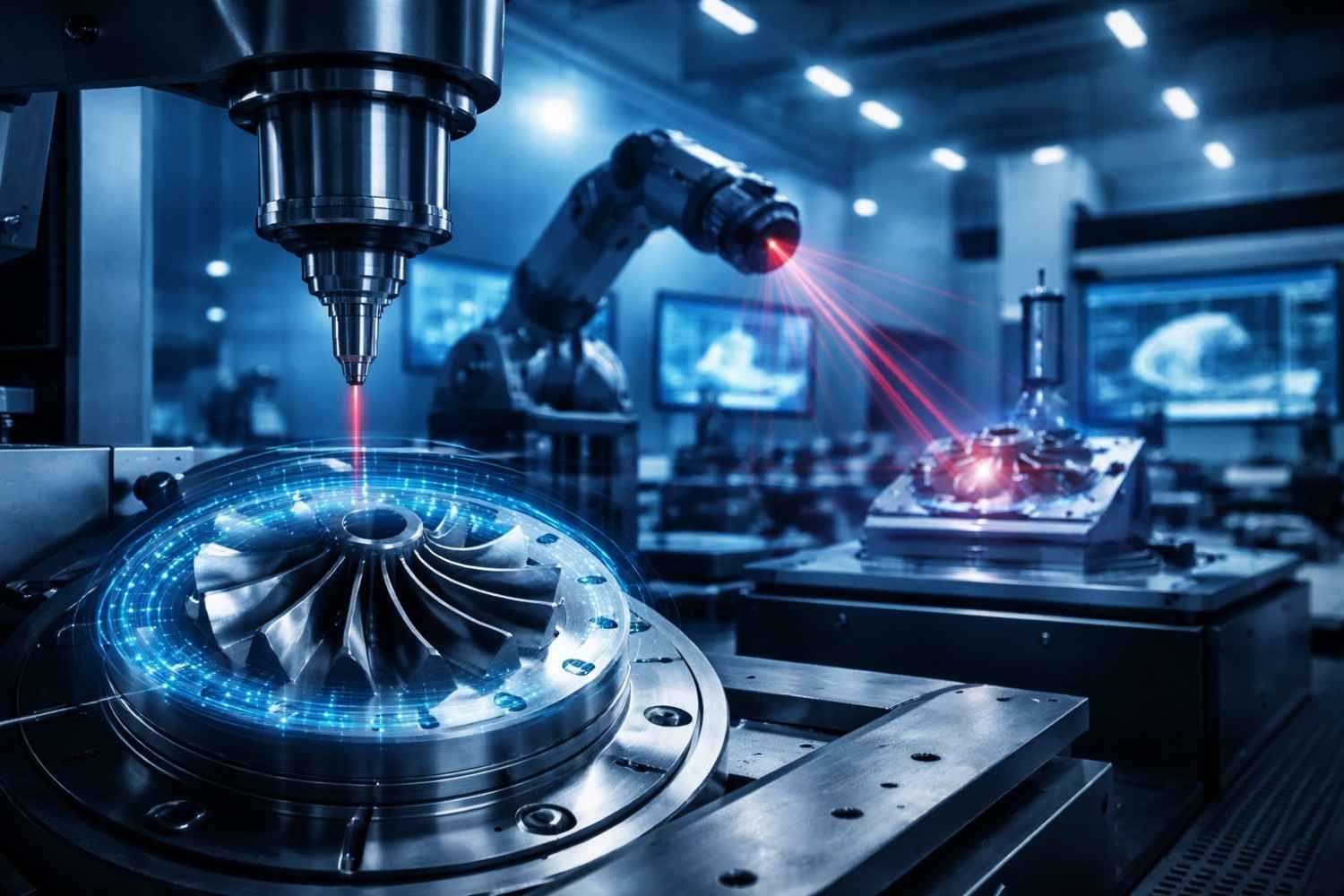

CNC Machining

Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining is the backbone of precision manufacturing. Unlike manual lathes or mills, CNC machines interpret digital code to move tools along multiple axes simultaneously. High-end 5-axis machines can approach a workpiece from virtually any angle, allowing for complex geometries without the need to re-fixture the part. This reduces setup errors and ensures that the relationship between different features remains perfect.

Laser Interferometry

When positioning a machine tool, how do you know it moved exactly 10 microns and not 10.5? Manufacturers use laser interferometry. This technology splits a beam of light to measure distances with wavelengths as the ruler. Because the speed of light is constant, this method provides the ultimate feedback loop for calibration, ensuring that the machine knows exactly where it is in physical space.

Precision Lapping

While CNC machines remove material to create shape, some applications require surface flatness and smoothness that a cutting tool simply cannot achieve. This is where precision lapping comes in. It is an abrasive process where a part is placed between two rotating plates with a slurry of abrasive particles.

Lapping is less about aggressive material removal and more about refinement. It creates surfaces so flat that they can form airtight seals without gaskets. For industries requiring optical clarity or high-pressure fluid control, precision lapping is the bridge between a “machined” surface and a perfect one.

The Critical Role of Climate Control

You can have the most expensive CNC machine in the world, but if you put it in a hot garage, you will never achieve micron-level accuracy. The enemy of precision is thermal expansion.

Materials grow when they get hot and shrink when they get cold. Steel, for example, expands roughly 6.5 millionths of an inch per inch of material for every degree Fahrenheit increase in temperature. On a large aerospace part, a temperature swing of just a few degrees can cause the metal to expand beyond the allowed tolerance.

To combat this, high-precision manufacturing facilities effectively operate as clean rooms. They utilize sophisticated HVAC systems to maintain temperature stability within ±0.1°C.

It isn’t just the air temperature that matters; it is the thermal stability of the machine itself. Modern equipment often includes liquid-cooled spindles and frames made from materials with low thermal expansion coefficients, such as granite or specialized ceramics. By treating the environment as part of the tooling, manufacturers eliminate the invisible variable of heat.

Overcoming Challenges in Sub-Millimeter Precision

Achieving accuracy on a prototype is difficult; achieving it on a production run of 10,000 units is a monumental challenge. Manufacturers face a constant battle against physical variables that threaten consistency.

Vibration is a primary culprit. A forklift driving past a machine or a heavy truck on a nearby road can send microscopic tremors through the floor, ruining a surface finish. To counter this, precision machines are often mounted on “floating” concrete foundations isolated from the rest of the factory floor, or on active air-suspension systems that cancel out incoming vibrations.

Tool wear is another inevitability. As a drill bit or cutting insert engages with metal, it slowly degrades. A dull tool pushes against the metal rather than slicing it, creating heat and deflection. Advanced monitoring systems now track spindle load and vibration signatures to predict exactly when a tool is about to fail, prompting an automatic change before the part is compromised.

Material stress also plays a role. When you aggressively cut metal, you induce internal stress. When the part is released from the clamps, it can spring back or warp, losing its shape. Manufacturers must use stress-relieving heat treatments and strategic machining paths to ensure the material stays stable after it leaves the machine.

The Future: AI and Closed-Loop Manufacturing

The next frontier in precision is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Currently, most quality control happens after the part is made. If a defect is found, the part is scrapped, and the process is adjusted.

AI and machine learning are moving the industry toward “closed-loop” manufacturing. In this future state, sensors inside the machine will detect minute variations—a slight temperature rise, a tiny vibration in the cutter—and the AI will adjust the machine’s parameters in milliseconds to compensate.

Rather than checking for quality at the end of the line, the system ensures quality during the process itself. This shift will reduce waste, lower costs, and push the boundaries of accuracy even further, making today’s impossible tolerances tomorrow’s standard.

Conclusion

Micron-level accuracy is the invisible force behind the reliability of the modern world. It is what allows cars to drive hundreds of thousands of miles and surgeons to perform robotic procedures with confidence. As industries demand smaller, more efficient, and more powerful devices, the manufacturing sector will continue to innovate. By combining robust mechanical engineering with environmental stability and intelligent software, manufacturers are not just building parts; they are defining the limits of what is physically possible.